-

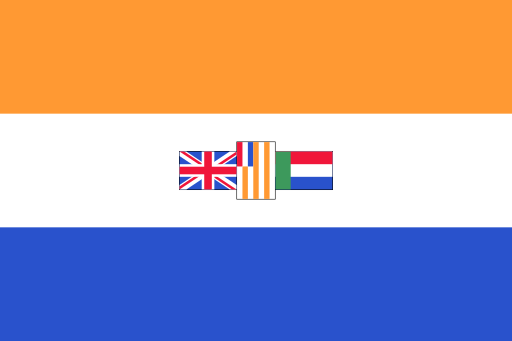

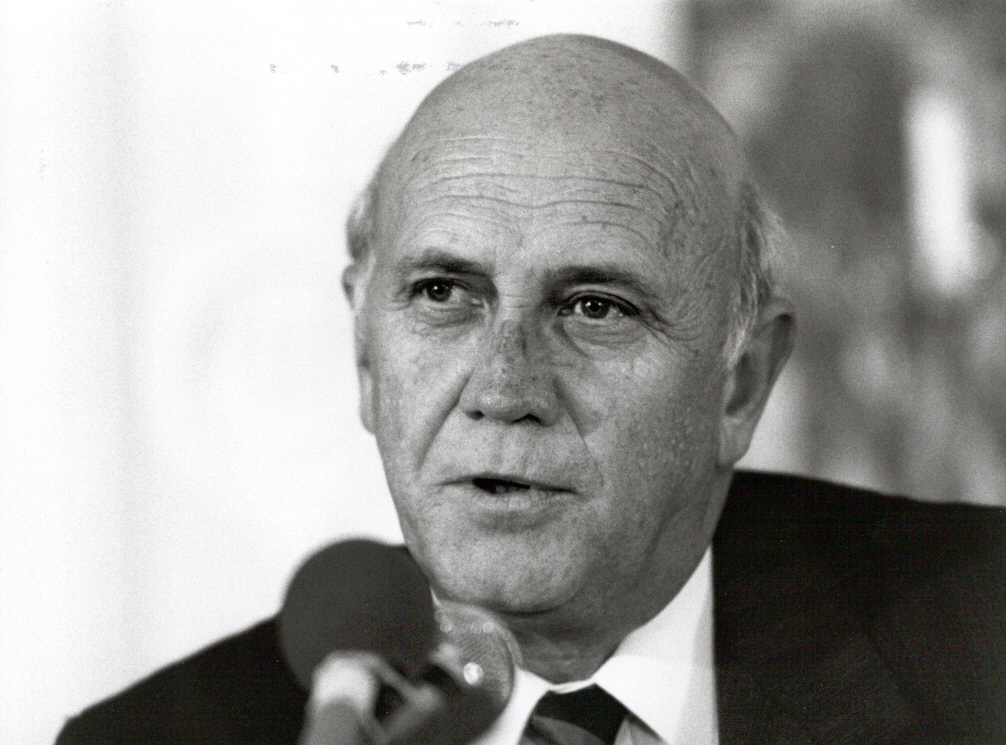

Did de Klerk deserve a Peace Prize

Were the President’s reforms a genuine push for racial equality, or just a bid to stay in power?

In 1993, Frederik Willem de Klerk, then President of South Africa, was jointly awarded a Nobel Peace Prize alongside Nelson Mandela, world-famous revolutionary and his soon successor, for their collective service in dismantling the much despised Apartheid regime which had kept their country racially segregated for over four decades. Whether his part in this was truly substantial enough to warrant such an honour is somewhat disputed.

Certainly, de Klerk was responsible for massive social reforms during his presidential tenure: in his first parliamentary speech he legalised opposition groups such as the African National Congress, the Pan-African Congress and the South African Communist Party, as well as releasing their high profile leaders. He also pledged towards improving the status of non-whites and achieving racial equality, even though this went against his natural beliefs.

The results of de Klerk’s decisions were extreme – by 1992, all of the laws regarded as stemming from the Apartheid system had been repealed and by 194 the country was ruled by a member of the majority race for the first time in its history.

Yet there is also a strong argument for the case that de Klerk was not a true egalitarian (for sure, he considered himself right wing even by Afrikaner standards) and that his reforms were merely a desperate reaction to the crises across South Africa: the country was torn by riots, strikes and protests. A civil war was a real possibility by the time of Botha’s resignation, and the National Party – which had governed the country since 1948 – was losing ground in the polls to the Conservative opposition. Also a pressing concern was hat the financial meltdown of 1985 has left lasting damage to the economy, and the thawing of the Cold War under Mikhail Gorbachev meant that Western powers were no longer incentivised to put up with South Africa’s deplorable policies for the sake of economic security – or, indeed, the avoidance of a potential communist takeover. Therefore, all of de Klerk’s reforms could be viewed simply as a cornered politician attempting to maintain his power.

This view, however, ignores the fact that His Excellency almost willingly gave up his power to Mandela by allowing blacks to vote in the 1994 election. Certainly, he made some attempts to stay within the political sphere, such as the power sharing agreement which allowed him to step down one rank instead of leaving the government altogether, but arguably that could have been for the sake of political stability. In any case, the idea had been the suggestion of a leading communist! To add to this, de Klerk actually pushed social reform far further than most people expected – rather than a few token concessions like those of Botha before him, de Klerk set about completely overthrowing the old system and embracing equality. He was far more respectful of Mandela than his predecessors had ever been and the two were able to make good use of discussion. I would say that his ability to commit to all of this despite being naturally inclined to preserve the ways of segregation actually shows he had more moral fibre and sensibility than most politicians then or now.

In any case, it should be remembered that the operative word in his prestigious award is “Peace”. Had de Klerk continued with Apartheid for much longer, there almost certainly would have been a civil war, if not a military intervention by other countries to effect political change, the repercussions of which could have been severe. The fact that F.W. used his position of power to take the necessary steps in avoiding this demonstrates that he indeed deserved the Nobel Prize.

-

The Hepatic Portal Vein

The hepatic portal vein is a large blood vessel, which carries nutrient-enriched blood to the liver. The vein (in adults) is around 8cm in length, beginning behind the neck of the pancreas and ending in several divisions at the liver.

This vessel is alternatively known as the splenic-mesenteric confluence, because it comes into being when the splenic vein (which collects blood from the spleen) and the superior mesenteric vein (which collects blood from the small intestine). Later, the vein also combines with the gastric and cystic veins, which take in the blood from the stomach and gall-bladder, respectively.

When the hepatic portal vein reaches the liver, it divides to make two portal veins, left and right. These smaller veins further divide until they become portal venules, which deliver blood into the liver sinusoids (permeable capillaries).

The purpose of the hepatic portal system is to supply the liver with 70% of its blood and 50% of its oxygen. By taking nutrient-rich blood from the spleen, stomach, gall bladder and small intestine, then transporting it to the liver, the hepatic portal vein allows the liver to process nutrients from all around the body and to filter out ingested toxins.

Sources: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hepatic_portal_vein; www.merriam-webster.com; encyclopedia brittannica; radiopedia.org; www.imageradiology.blogspot.co.uk

-

Wonder and Enchantment in “The Tempest”

How does Shakespeare explore this theme in Act 4?

How does Shakespeare explore this theme in Act 4?In the penultimate scene of his ultimate play, the famous bard writes of how two young lovers, Miranda and Ferdinand, are gifted with Prospero’s magic on the acceptance of their union. As a pre-wedding present to the future couple, the deposed Duke puts on a masque – a grand display of light and dance by his spirits.

The leading players in this wondrous performances are Iris, Juno and Ceres. Iris, in Greek mythology, was a messenger from the heavens, a rainbow personified. Iris is regarded as a communicator, the ambassador between mortal men and the divine, and so her presence in the masque makes sense, as she is helping the couple acquaint themselves with the ether world, as well as to understand the power of Prospero. The masque also features Juno, normally a warlike figure, repurposed to symbolise marriage – for in her first line she pledges “to bless this twain, that they may prosperous be, and honoured in their issues”, the final noun meaning Miranda’s potential children, the future rulers of both the Kingdom of Naples and the Duchy of Milan. The third spirit is Ceres, goddess of fertility, who delivers in more artistic terms a similar message that “scarcity and want shall shun you”, meaning that they should be well-nourished and never hungry or poor. The double meaning of Ceres’ verse in lines 110-117 is encouragement for the lovers to bring up many offspring (a process often described in the form of agricultural metaphors).

The beauty of this entire spectacle is apparently great enough for Prospero, the great magician, to be mesmerised by his own tricks, as he says from line 139 “I had forgotten that foul conspiracy of the beast Caliban and his confederates against my life. The minute of their plot is almost come.” then

quickly shoos the goddesses away and ends the masque abruptly, leaving Ferdinand quite perplexed. What is interesting about this aside is that, compared to the long, flowery metaphors of the songs that had dominated the previous pages, this is written plainly (normal for 17th century England, if not for today’s audience). When Iris clarifies the warning against fornication, she says “no bed-right shall be paid… [Cupid] has broke his arrows, swears he will shoot no more…”, explaining it all in terms of Greek and Roman religious characters, yet Prospero comes to his senses with a clear and concise reminder of the real-life events unfolding. To write the speech in this way neatly highlights the boundary between the two different worlds which Prospero must juggle – one can afford to be whimsical and artistic, while the other has more pressing practical problems to deal with.

It appears that, until the premature conclusion, the spirits’ performance impresses Ferdinand and Miranda. The former asks if he “may be bold to think these spirits” in a way which shows his fascination with what he sees, yet he later clarifies that “a wonderful father, and a wife, makes this place paradise”. As if to convince Prospero that he remembers his true objectives, and appreciates the present while remembering that his new family is integrally important.

Throughout the entire masque sequence, Ferdinand has only two brief pieces of speech, and Miranda is silent. Perhaps this could show how the audience too should be enchanted by this charade, enough to forget the human characters, or indeed to feel that they are the observers, and that they have been themselves pulled into the scene, only to be suddenly snapped out when Prospero does.

All of which brings us to the other side of Act 4 – the events with Caliban, Trinculo and Stephano. There are many attempts to juxtapose their situation with that of the trio above. For instance, while Prospero, Miranda and Ferdinand are on the surface, gazing out to the heavens, the conspirators are underground engaged in petty squabbles. This is summed up by Trinculo’s comment: “Monster, I do smell all horse-piss, at which my nose is in great indignation”. This highlights the different outlooks that these characters have on the world: Whereas the glittering prose of the spirits (such as “to make cold nymphs chaste crowns” or “Mars’s hot minion is returned again”) is meant to display a vast fountain of intellect and wisdom, the inebriated jester’s rather profane description of his immediate environment demonstrates a more low-brow approach to life.

That impression further rings true when they encounter the “glistening apparel” laid out by Ariel to catch them. Upon seeing the fancy clothes, Trinculo exclaims “Look what a wardrobe is here for thee!”. He and Stephano then experience wonder and enchantment on a different level as they try on the wealthy garments. Only Caliban, whose material tastes are rather more utilitarian, seems to be aware of the trap, while the other two are totally infatuated with the clothes. The fact that they instantly proclaim themselves as kings is evidence of their unworthiness to take such a position for real. After all, the Crown Prince of Naples is at this point rising above fashion and money, while they are drunkenly squabbling over stolen robes.

Indeed the whole of Act 4 overall demonstrates the stark contrast between what different types of people find truly wondrous or enchanting, and it shows that it is the better man who finds such thoughts in higher, more noble pursuits than the one who should make a priority of obtaining what is, in the grand scheme of things, a rather petty desire.

-

Putting Pressure on Apartheid

Which was more important in putting pressure on Apartheid up to 1976; black resistance or international pressure?

Although initially slow to respond to the plight of the blacks, the developed Western world had, by the latter third of the twentieth century, come to strongly oppose the Apartheid regime in South Africa. Beginning in the early 1950s, many world leaders, public figures and ordinary people carried out campaigns to effect political change in the former colony which would equalise the civil rights of all four racial groups. How effective this campaigns were remains a matter of debate.

The bulk of international pressure came in the form of boycotts, economic sanctions and charitable donations to those on the inside, along with much verbal condemnation of the white oppressors. This was particularly apparent in the world of sport, as South Africa was banned from the Tokyo Olympic Games in 1964, and many international sporting tours involving South Africa were either cancelled by the foreign parties or disrupted by protesters. Another key area was international trade: companies which invested in the South African government or which imported South African goods were continually shamed and boycotted. Unfortunately, these actions – while certainly raising awareness of the issues – had little practical effect in terms of convincing the National Party to change its policies. This was mainly due to a general unwillingness, or indeed inability, for many governments and companies to fully cut their ties with the backward republic. Although far below European nations or the “big three” in global power rankings, South Africa was relatively well-off by the standards of its part of the world, and many big players in the global financial system were afraid to risk jeopardising their investments their. General Motors, for instance, eventually convinced their South African trading partners to respect the rights of non-white employees within the context of joint business ventures, but stopped short of demanding nationwide reforms. Barclay’s Bank, too, continued to profit from economic growth in the country – despite protests in the West – and the developed world as a whole found that they still needed to trade with South Africa, upon whose ports, raw minerals and shipping channels they remained dependent. The end result was that the Apartheid government was in little danger, and remained stubborn.

At a higher level, the United Nations, which included many other former colonies now run by the black population, repeatedly ordered the abolition of what it thought to be a major human rights violation and a crime against humanity. Yet the South Africans took no notice. The main reason for this was that, with the red cloud of communism ever looming over Western heads from the Soviet Union, no country dared to attempt military action against the South African government for (mostly unjustified) fear that an important trading partner might become politically unstable and open to takeover by a communist uprising. In any case, the countries immediately surrounding South Africa were also white-ruled, so a tactical strike would be a difficult and costly process. Again, this meant that the international community could do little to threaten the racist government’s security.

Compare this with the black resistance inside South Africa: the African National Congress and Pan African Congress were able to strike directly at the government by means of boycotts, strikes, rioting and sabotage. Though the police of the regime often fought back with legal force, this fact merely proved that the government felt truly threatened by black rebels. This all culminated in the Soweto riots, in which the government’s control of the region was permanently weakened and the size of the resistance movement increased massively. Somehow the message evidently got through, as by 1978 the government finally took steps to rectify the problems which the non-whites faced.

An interesting point to note, however, is that many of the measures taken by the activists within South Africa were supported from the outside. An example of this was the International Defence and Aid Fund, which paid for legal assistance for black leaders in South African courts. It could be said that, if not directly responsible for the end of Apartheid themselves, the people of the developed world did at least achieve much in bolstering the effort from behind the scenes.

Overall though, the success of the anti-apartheid movement was by and large down to the South African non-whites fighting to save themselves, as only they were truly committed to bringing down the regime at any cost and were not held back by the sometimes petty economic and political fears which blighted western attempts. Whether the ANC and PAC would have succeeded alone, without the monetary backing of foreign donations, will ever be debatable, but we can be fairly confident that it was not the most crucial part in events.

To conclude, black resistance was the most important in putting pressure on Apartheid up to 1976 – though a little help from distant friends certainly did not go unnoticed.

-

Nature versus Nurture in “The Tempest”

Shakespeare’s final masterpiece presents the readers and viewers with a range of characters, each of whom has a personality and set of abilities. Some such aspects are assumed to be innate, and to exist simply because of who they are. Others are explained to have been developed by the experiences that the characters have enjoyed and endured in the years leading up to the play’s events. Sometimes, the supremacy of either in regards to the personalities of each character can be the subject of much debate.

Shakespeare’s final masterpiece presents the readers and viewers with a range of characters, each of whom has a personality and set of abilities. Some such aspects are assumed to be innate, and to exist simply because of who they are. Others are explained to have been developed by the experiences that the characters have enjoyed and endured in the years leading up to the play’s events. Sometimes, the supremacy of either in regards to the personalities of each character can be the subject of much debate.The character of Caliban is, from his initial introduction in Act 1 Scene 2, bestowed with many dislikeable qualities and attributes. He is portrayed as scaly, uncivilised, barbaric and morally deficient. Prospero describes him as a “poisonous slave” while Miranda calls him “savage”. Both seem to be convinced that the man to whom they refer is beneath them; that Caliban is sub-human and not deserving of the same respect that they are. Many critics of the play have historically associated this theme with racism of the time – particularly as Caliban is often portrayed by a black actor in an otherwise white cast – but there are also reasons given for the creature’s low status which stem from his own actions, most notably the fact that he “…did seek to violate the honour of [Prospero’s] child.”. Whether this act was a deliberate sexual assault or a dire misunderstanding is left ambiguous in the play, but what matters is that it shows the treatment of him was based on his own actions – indeed, the characters speak of a time when relations were rather warmer, and when a then innocent Caliban was accepted almost as an equal (though accounting for his lack of formal education).

Moving on to Prospero’s character, we find more unanswered questions as to the subject of this essay. The most prominent is that of the former Duke’s magical abilities. What is not discussed is whether or not his powers are derived from a gift he possessed at birth. It is said that Prospero learned magic from studying the relevant books in his vast libraries – with the implication that any sufficiently dedicated scholar could do the same, yet he is sometimes portrayed as an almost otherworldly being.

To discuss “nurture” in the more literal sense, we must look upon Miranda. It is clear from their interactions that Prospero – strict and powerful as he is – cares deeply for his daughter’s wellbeing and happiness. Unfortunately, she is forced to live out most of her childhood in a very strange place, with only her father, Caliban and Ariel for company. She only dimly remembers her early years in Milan, which “’is far off; and rather like a dream, than an assurance that [her] remembrance warrants.”. This surely would have a great impact on her development. Upon her meeting with Ferdinand, Prospero reminds her “Thou think’st there is no more such shapes as he, having seen but him and Caliban. Foolish wench,” – meaning that her lack of familiarity with males her own age leaves her with no mechanism for properly judging the prince’s character, making her easily impressed by relatively weak charms and therefore vulnerable. Of all of the characters in this play, Miranda is the one who is most a product of her unique experiences, for it seems that her life – and thus her personality – would otherwise have been very different.

Upon leaving the world of humans, we come to the mystical spirit Ariel. His “nature”, as it were, is difficult to define, given the myriad ways in which the character has been depicted throughout various performances of The Tempest. Sometimes he is shown as a large anthropomorphic bird, others as a musical eccentric or a naked adolescent. His lines show him to be a creature of the elements, rather than a physical organism. His “nurture” consists of his torment, imprisonment and abandonment by the witch Sycorax, followed by his rescue and employment by Prospero. Though he appreciates the latter’s relative kindness, still he longs to be released back to the sky where he truly belongs. Oddly however, he seems to take an unusual pleasure in carrying out the tasks Prospero has set him, such as when he graphically recounts his imaginative creation of the titular storm (“Now in the waist, the deck, in every cabin, I flamed amazement…”), or when he poetically tempts the various shipwrecked royals. In all such cases, there is insufficient information to determine whether this is natural for a being such as him (if indeed there are others) – yet one can perhaps make an educated guess and suggest that his ethereal mannerisms are inbuilt, but his desire to please is brought on by his gratitude to Prospero, combined with the need to win his favour so that permanent freedom may be granted.

Overall it is fair to say that the early part of this play features many displays of both innate characteristics and those which are clearly the product of upbringing or life experience. I would not suggest that this is the central theme of the play, nor that Shakespeare ever comes to a definite conclusion on which he thinks matters most (at least not within the first two acts), but it can be said that he endows this early part of the script with many reminders of both ideas and layers of subtext regarding how each of the major characters is made up of a combination of both.

-

Hyperbaric Chambers

How do hyperbaric chambers work and how can they be used?

A hyperbaric (high pressure) chamber is a closed container, sufficiently large to house a human body. A chamber contains its own supply of compressed air. Controlling the release of this air allows the inside of the chamber to simulate different levels of atmospheric pressure from the outside.

A hyperbaric chamber is typically split into three parts: The first is the pressure vessel in which the occupant is held; the second is the pressure supply (a source of highly pressurised gas); the third is the oxygen supply.

The main use of a hyperbaric chamber is in hyperbaric medicine to treat decompression sickness in divers (dissolved gases bubbling inside the body after it surfaces too quickly). Keeping a patient in a high-pressure atmosphere with a more oxygen-rich air supply eliminates the bubbles and helps the body to recover. For other maladies (including burns, anemia crush injury and gangrene), hyperbaric oxygen therapy speeds up the body’s natural healing systems, because it increases the amount of oxygen absorbed in the blood and carried to other organs.

Outside of medical areas, a hyperbaric chamber can be used as a training tool for divers (particularly in Naval Forces), as it allows them to acquaint themselves with a high-pressure environment and there test their physical performance.

Impersonal chambers are also useful in the field of scientific research, as they can be used to find out if organisms or chemicals behave differently when the pressure around them is altered.

Sources: ehow.com; livestrong.com; sciencedirect.com

-

Agent Orange

What it contained and how it worked.During the Vietnam War, the United States military embarked on a chemical warfare program (known as “Operation Ranch Hand”) in the hopes of uncovering Viet Cong soldiers by destroying the vegetarian under which they had hidden.

Agent Orange is one of the most (in)famous chemicals used. It was an even mixture of two compounds, 2-4-D and 2-4-5-T.

2-4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (C8H6Cl2O3) is a synthetic plant hormone which is absorbed through the leaves to cause death by massive overgrowth and subsequent withering. The auxin is used commonly as a weedkiller in America.

The other half of the Agent, 2-4-5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid, was a similar substance. It too is a synthetic auxin intended for use as a herbicide, but has been long banned due to health concerns. While not especially toxic in itself, it is often contaminated with a far more harmful substance during manufacture (2-3-7-8-Tetrachorodibenzodioxin, or “Dioxin”). TCDD is highly carcinogenic, and has been known to affect how different genes are expressed in certain organisms. It cannot cause cancer alone, but can increase the risk from other carcinogens which are also present.

The use of Agent Orange in Vietnam caused widespread health problems for plants and animals. There were 400,000 deaths caused by the campaign and 500,000 deformed newborns. Traces of dioxin were found in the breast milk of Vietnamese mothers, and many residents in the affected areas today still carry genetic diseases.

Sources: www.science.howstuffworks.com; www.poisoned.homestead.com; www.en.wikipedia.org

If you are interested in other aspects of the Vietnam War, why not see this essay.

-

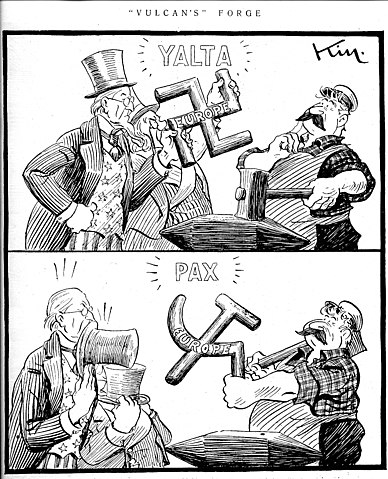

Cold War: The Actions of Stalin

An essay on the extent to which we agreed with the statement “The Actions of Josef Stalin between 1945 and 1949 were the main cause of the Cold War”

An essay on the extent to which we agreed with the statement “The Actions of Josef Stalin between 1945 and 1949 were the main cause of the Cold War”It is certainly true that Josef Stalin was a devious and power-hungry figure. He accomplished his original rise to power, from a lowly background figure in the Russian Revolution to undisputed champion of the Bolsheviks and commander of the Soviet Union, by cunning rather than charisma. Many of his (perhaps more worthy) opponents in the political scene were simply removed, and the empire was purged of any potential threat to its leader.

Although ultimately he took the “good” side in WWII, fighting alongside Roosevelt and Churchill to crush the Nazis, it was no secret that he remained no less evil than Hitler, whom he indeed had at first planned to side with so as to take on Britain and America. It is therefore not implausible to suggest that, in the aftermath of “The Great Patriotic War”, he had been planning not only to “protect” the USSR from another German attack through Eastern Europe — a valid point though that was — but to expand the borders of the USSR’s territory further west and spread Soviet influence across the countries for whom capitalism had failed (finally achieving, perhaps, Trotsky’s old aim of Socialism in Many Countries and Permanent Revolution). This indeed appeared to be the case, as by 1948 he had successfully installed puppet governments in Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Hungary and Albania. These countries formed the “Eastern Bloc” of Soviet satellites which extended Stalin’s power across Europe. Source 5 clearly supports this case, depicting Stalin swiping the whole of the continent, and casually reaching to add most of Asia, while Source 12 shows Stalin the cat beating up Eastern European mice. The former was drawn in Chicago shortly after Yalta, and reveals the American perspective of what the Big Three were planning. The latter was made in Britain, 1948, after much of the Eastern Bloc’s absorption into the USSR had taken place. Between them, they thus seem to show the prediction and confirmation of what, to the West, was an attempt bye Stalin at world domination.

However, the United States was not unanimously seen as particularly innocent either. Just as Soviet influence swept across the East of Europe, American influence swept across the West. Alongside the establishment of socialist government and collectivist business models in East Germany, the Western side was being plastered with advertisements consumer goods, and high streets became temples to US-style consumerism. While Truman stated that the Marshall Aid plan was purely intended to help broken European nations recover from the effects of Nazi occupation, many Soviets saw it as him attempting to establish a loyal base in Western Europe from which to attack the USSR, and so thought that the “buffer zone” of Eastern Countries was purely for defensive purposes.

It could be said that this caused a mutual defensive complex between Truman and Stalin. Each thought that the other would be striving to absorb territory around their own countries, eventually aiming to conquer the entire planet and force their economic systems upon everybody. To prevent that, each side began to bribe or coerce small, potentially soluble governments in weaker countries to maintain that side’s ideology and to become strong enough not to “fall” to the other side’s influence. Of course, it was only the enemy power that was using imperialist bullying tactics, the “good” side was merely using its power to protect the weaker countries and keep the enemy at bay. If that meant having to dominate the politics and economics in east/western Europe and occasionally order other countries around, so be it.

Source 1 neatly summarises this idea. Though rather abstract and lacking in specific details, “striking out for advantage or expansion” was entirely true of both powers during the Cold War.

In the formative years of the Cold War, Anglo-American interference featured heavily in the events of Eastern Europe. A notable example was the Greek Civil War, in which the UK and USA successfully defended the Royalist side against a potential communist takeover. Truman insisted that he was keeping the Greeks free from totalitarianism — an idea which many Soviets dismissed as American propaganda to justify stealing power and territory from the USSR (as seen in Source 11) .

Another crucial part of the cracks in international relations during this period was the role played by the development and successful deployment of the Atom Bomb, mankind’s first true “Weapon of Mass Destruction”. Even Truman himself was not initially aware of this, remaining informed about the project until the Potsdam Conference, at which point there occurred a paradigm shift in the way he —and subsequent US presidents- viewed world politics. Winston Churchill reports in Source 6 that after Truman (unbeknownst to him or Stalin) was quietly told about the successful bomb test, he underwent a then-inexplicable change of character, suddenly assuming a much more authoritative stance over the foreign delegates, “… [telling] the Russians just where they got off and generally [bossing] the whole meeting.” secure in the knowledge that he had become easily the most powerful man at the table. Source 9 well represents the general picture of American foreign policy at this point: Truman is shown asking Attlee and Stalin why the UK, US and USSR could not “…work together in mutual trust & confidence”, while clutching the “private” bomb behind him. It seems that Truman at this time considered normal diplomacy to be a frivolity in terms of getting what they wanted from the world, one rendered unnecessary by the emergence of a new political tool: the fact that the United States possessed Weapons of Mass Destruction whereas the Soviet Union didn’t…until the point at which, suddenly, they did.

Following the dropping of the atomic bombs unto Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the scientists in the Soviet Union soon developed their own nuclear weapons with which to remove the USA’s advantage. This began an arms race between East and West which lasted for several decades, and which sparked the production of Weapons of Mass Destruction in other wannabe-world powers today. Among the main pillars of the unease between nations, and integral to the existence of the Cold War, was the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction; either side having the power to destroy the other —and the rest of the world-within minutes. Without the atomic and later hydrogen bombs which reinforced MAD and therefore kept tensions high, it is unlikely that the USA and USSR would have been in such deadlock for so long, instead either declaring true war using conventional means or resolving their problems diplomatically.

This, however, concerns the long-term effects of the bombs. In the short term, it seemed more likely that they would indeed be used as the flagship weapon of an upcoming Russo-American war. Source 8, from the memoirs of Marshal Georgii Zhukov, says that Stalin wanted to “‘…speed things up’” which was interpreted as a desire for to accelerate the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons research. While future Soviet dictators were more conservative in the levels of mass annihilation they were prepared to wreak, Stalin was apparently prepared to use nuclear force to destroy the USSR’s main enemy.

There is yet another school of thought to this entire debate: that such a deadlocked “war” between the USA and the USSR was inevitable, no matter what events took place prior to it. Americans and Soviets were too different from each other, the reasons for which lay in the ideologies by which their respective countries were originally established. Oddly, both believed themselves to be the best for the common man, though in different ways. The American philosophy stated that anyone, given the opportunity, could turn their ideas into vast sums of wealth, and live a comfortable life. The Marxist philosophy, meanwhile, dictated that there should be no individual wealth, that all property should be owned by the state, and that all people should be equal.

The United States of America were — and remain to this day — the model of Free-Market Capitalism. Business, corporations and profit have been seen as the defining trait of the American way of life. Although there are many strong capitalist nations around the world, it has long been the United States which represents the pinnacle of it and all related ideas. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, on the other hand, only came into existence because the Russian Empire was a prime example of capitalism and right-wing politics failing. The nation born to Lenin, Trotsky and the other Bolsheviks from 1917 to 1924 was therefore made into the benchmark of Communism and Collectivism. Again, nearly all creations of socialist states in history were inspired, seeded by or modelled on the USSR.

The result of this was that Russia and America became polar opposites of each other. This, though, should not alone have been enough to lead to a potential war. After all, the two countries and their spheres of influence were huge enough to be self-sufficient worlds of their own, so surely Truman and Stalin could have gone about their business without disturbing each other. The real problem lay in the fact that neither the main proponents of Capitalism and Communism, nor the founders of them were content to stop there. Both saw their way? life as the only true solution to mankind’s problems, and the alternative as the root of all evil. Lenin and Marx had long been convinced that the human greed behind Capitalism was the cause of all wars, and that the lust of one person for profit could only be fulfilled as a result of taking wealth from someone else, that the rich survived by exploiting the poorest. Most Americans believed instead that Communism would lead to the unaspiring masses leaching from the best of humanity due to the lack of incentive to work hard and create something, to the end that society as a whole would stagnate, with no real driving force behind the improvement of life. (The American viewpoint is best expressed in Source 3, in which Truman describes capitalism as everything good, and communism as everything evil.) Ultimately, both have proven to be legitimate concerns about serious problems, but in the late 1940s, none were apparently serious enough.

By means of capitalism and profiteering in the form of businesses driving industries and industries driving profits, the United States had become incredibly rich and powerful. Meanwhile, by means of communism and Marx/Lenin/Stalinism in the form of collective agriculture and heavy industry, the Soviet Union had also become very rich and powerful. In fact by mid-I945 (when Britain and France, the last bastions of European imperial might, were clearly on their last legs), they were emerging as the richest and most powerful nations on Earth. This presented a problem: communists firmly believed that capitalism was fundamentally unstable, and doomed to failure, and vice versa. Yet clearly this was not the case, as both systems appeared to be thriving. So it was that the mere existence of each superpower was an insult to the other’s core principles. Source 17 sums this up, saying that “…the conflicting and unyielding ideological ambitions were the source of the complicated and historic tale that was the Cold War.” and Source 16 agrees that “The Cold War was caused by the conflicting interests of the United States and the U.S.S.R. … [which] led to the unravelling of the new international order nearly established in Roosevelt’s wartime conferences with Churchill and Stalin.” and Source 15 (referring specifically to the bomb, but applicable generally) describes the USSR as “… a nation who practised a political ideology different from America, which was unacceptable to the “free democratic” United States…”. All three were posted online after the Cold War ended, and reflect a sense of mutual guilt between Russians and Americans about everything that happened.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that the titular statement is true only in a very literal sense. The actions of Josef Stalin between 1945 and 1949 were the main cause of THE Cold War, that is, the Cold War which unfolded in our history. That there would have been A Cold War of some description was inevitable, due to the ideological incompatibility of Americans and Soviets as described above. This particular version of events, however, was dependent on Stalin’s actions after the War. Had the Moscow Kremlin at the time been led by Trotsky, Bukharin or any other potential successor to Lenin, perhaps different moves would have been made. Perhaps different boundaries would have been drawn up so that Germany was not turned into a political battleground for four decades, due to the USSR being content to regain its own territory rather than expanding beyond them, or even pushing further westwards to dominate the whole continent. Perhaps both sides could have negotiated joint power over broken Europe, forming a mixed political set-up rather than splitting countries up and moving them further apart economically. Perhaps the USA could have been talked out of nuclear strikes, dampening the fire behind the arms race. No matter what happened at that point, however, the Cold War could only have been delayed or reshaped, never averted. It would always have taken place in some form, because neither side could be satisfied until the other totally ceased to be, which is why it seemed that all of the problems simply melted away when, finally, one side gave in and did just that.

-

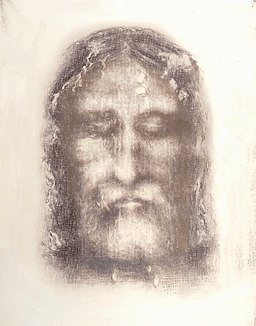

Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud

An investigation into the validity of the claims made about the age of the Shroud of Turin.

The Shroud of Turin is an artefact whose age remains a controversial subject. It is a large piece of cloth, bearing the image of a man who appears to have been crucified. Many believe that the image is of Jesus, and that the shroud is the one in which he was buried after his execution by the Romans. Using the prevailing consensus on the date of the crucifixion, this would make the shroud 1980 years old. However, when the shroud was radiocarbon dated, the results suggested that the shroud was much younger, having been created somewhere in the Middle Ages, no earlier than 1260 C.E.

(Radio)carbon dating is a method of determining an object’s age by determining the ratio of Carbon-14 and Carbon-12. C-12 is the standard, stable type of Carbon atom, whereas C-14 is an unstable form caused by the collision of Nitrogen atoms with cosmic rays in the atmosphere. All living things take in large amounts of carbon during their lives. Upon death, the amount of C-12 remains the same, while C-14 begins to decay and revert to nitrogen (the half-life is approximately 5730 years) so that newer artefacts will have similar amounts of C-12 and C-14, while older ones will have a proportionally smaller amount of the latter.

The shroud was carbon dated in the late nineteen-eightees, when it was suggested to have been produced in the thirteenth century. In 2005, though, a new investigation uncovered evidence to the contrary: It appeared that the particular patch of linen from which the 1988 sample was taken did not match the rest of the shroud. It appeared to be made of a more modern cloth, and to have been deliberately coloured to appear like the older parts. It also had higher levels of Vanillin, a compound derived from plant matter. The theory produced at this point was that the non-representative patch had been a replacement piece, woven in during the medieval period to repair fire damage to the shroud. When the cloth was re-tested, the age was estimated to be between 1300 and 3000 years. This would allow it to be from Biblical times. The issue of whether Christ was buried in the shroud, on the other hand, remains highly debated.

Sources: bbc.co.uk/news; wikipedia.org; hyperphysics.phymaster.gsu.edu; youtube.com/user/saamerican

-

Degeneracy, Universality and RNA

How RNA differs from DNA, plus explanations of the terms “Degenerate” and “Universal”

The term “degenerate”, when used in the context of genetics, means that a part of a genetic code is redundant. Degeneracy in DNA is caused by the fact that the different combinations of nucleotides add up to make 64 potential codons, yet there are only 20 types of amino acid used to make proteins. The resultant codon : amino ratio of more than 3 : 1 means that there are often two or more redundant codons in each amino acid. The more redundant pieces of code, the more “degenerate” the code is said to be.

DNA is said to be “Universal” because all living things currently known to exist contain a DNA structure consistent of deoxyribose sugars, nitrogen bases and phosphates. Thought the order of bases within a sequence differs between organisms, the fundamental materials which make up a genetic code are the same throughout known life.

RNA stands for Ribonucleic acid. Like DNA, it is a polynucleotide chain made up of four nitrogen bases and phosphate groups. RNA differs from DNA in that the former normally exists as a single stranded molecule, with a short chain of nucleotides, whereas the latter’s chain is longer and the molecule is always double stranded. The two also differ in terms of longevity: DNA is totally protected in the body cells and lasts so long as it can divide to reproduce. RNA, meanwhile, is repeatedly produced, destroyed and recycled. RNA does not replicate itself, but is manufactured in the body when necessary, based on existing DNA.

Chemically, one notable difference between DNA and RNA is that, though three bases (Adenine, Cytosine and Guanine) are common to both, the fourth changes between Thymine in DNA and Uracil in RNA. Another is that RNA uses Ribose sugars, whereas those in DNA are Deoxyribose – the difference being that deoxyribose lacks a single hydroxyl (OH) group present in ribose, replaced simply by hydrogen.

The purpose of DNA is to act as a medium for the long term storage of genetic information. RNA is only used for protein synthesis. mRNA is extracted from a DNA strand, and its codons are paired with the anticodons on a tRNA strand, resulting in an amino acid chain, rRNA then becomes part of the ribosome within a cell, which synthesise the proteins according to the code originally found in the DNA.

Sources: www.brighthub.com; www.bioinformatics.ni; www.enotes.com; www.buzzle.com