-

Balancing a Soft Drinks Can

An experiment with a 330ml drinks can to determine how much water is required for the can to balance on its edge.

A typical 330ml can, typically associated with soft drinks, can be made to balance on the edge of its bottom rim, provided the can is filled with a certain weight of liquid.

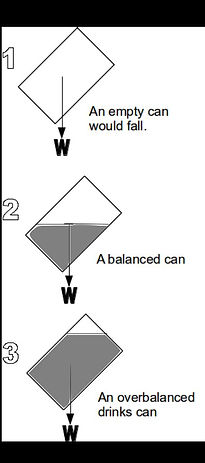

The reason for this is that the contents of the can affect the can’s centre of gravity. The centre of gravity is the point through which an object’s weight passes. If the weight acts over an object’s base, the object will remain in place. If the weight acts outside the base, the object will fall (1).

In an empty can, the centre of gravity is also the geographic centre. The addition of mass inside the can, however, shifts the centre of gravity, thus changing how the can balances. With the correct amount added, the CoG can be shifted to allow weight to still act over the base even when the can is significantly tilted (2).

If, though, too much mass is added to the inside of the can, it may push the centre of gravity back outside the base. This is because the increase in volume forces some of the mass to sit above the pivot point, thus cancelling the effect of the mass below.

In this instance, a can was filled with multiple quantities of water, and then tested to see whether it could balance. The results are shown below.

By process of trial and error, it was determined that the optimum range for the amount of water used is approximately 0.025 – 0.200 kg (or 25 – 200 ml), though the reliability of these results is questionable due to the accuracy of the measuring equipment, and the loss of water during transference. Based on the figures obtained, the mean amount of water to perfectly balance the can would be 0.1125 kg (or 112.5ml)

Water/kg Balance? 0.000 Too little 0.020 Too little 0.025 Yes 0.038 Yes 0.075 Yes 0.125 Yes 0.200 Yes 0.210 Too much 0.225 Too much 0.250 Too much -

Why Did the Cold War Start?

An essay on the beginnings of the conflict.

In the mid twentieth century, three superpowers dominated the geopolitical landscape: the UK, the USA and the USSR. These three countries had, recently, been working together to defeat a potential usurper power – Nazi Germany – from taking over much of the civilised world. It may have briefly appeared that the “Big Three” could remain firmly united by their victory, but soon it became clear that this could never be.

Perhaps more accurately, the Cold War was not a breakdown of the alliance, but proof that it never truly existed to begin with. The reason was that the great powers had achieved their status by very different means. The British had seen a wave of brand new technology far beyond its time invented so that they could maintain their vast colonial empire. The Americans had exploited their convenient bounty of natural resources to mass produce consumer goods to sell to each other. The Soviets had urgently industrialised out of a desire for mere survival against a less-than-friendly world. The most noticeable and thus most polarizing difference, however, was the contrast between capitalism and communism.

Britain and America believed in the ideology by which individuals – and companies – would work for their own personal or corporate benefit. They also believed in private property, the right to personal ownership of wealth, and the use of consumer goods to improve one’s standard of living. Under capitalism, society would advance because rival businesses would invent, design and sell better products to beat one another, and thus the goods and services available would forever evolve into superior versions of themselves.

The Soviet Union (as well – later – as China and North Korea) believed in a different ideology, whereby all people – specifically “the workers” – would cooperate for the benefit of everybody. They also believed in collectively owned property, the right to public distribution of wealth, and the rejection of consumerism. Under communism, society would advance because non-competitive innovators would invent, design and distribute better products specifically to better the lives of the people, with goods and services thus forever evolving as part of the quest to build a brighter future.

Also important was the difference in perception of the role that the government should have in people’s lives. Many Americans were opposed to “big government” and wanted the state to have as little power as possible, with responsibility for infrastructure and services delegated to smaller forms of government, or handed over to private industries. They also believed that virtuous individuals had earned the right to enjoy a higher standard of living, while lazy or careless people would be rightfully punished with one much lower. It was considered wrong for the government – and thus the taxpayer – to take responsibility for individuals’ personal decisions. Most communists believed that a large government was necessary to ensure that all people remained equal. They thought it unfair that some should live in lavish luxury while others starved. Under Marxist theory, only the communist state could understand “the engine of history”, meaning the eternal class struggle between the rich and poor. The state was believed to be an omniscient superpower, and the only establishment capable of managing the lives of the USSR’s entire population. The government was therefore to be given near total control over every aspect of people’s lives, thus ensuring that no individual could profit at the expense of another. Overall, then, the twin ideological peaks of communism and capitalism could hardly be more different, and nor could the personalities of those who followed them. Perhaps, if the two groups remained permanently isolated from one another, these differences would go largely unnoticed, or at least unremarked upon, so they could peacefully co-exist with relatively little friction. The decisions made at the Yalta and Potsdam conferences, however, meant that this was no longer possible.

When Winston Churchill, Josef Stalin and Franklin Roosevelt met at the Summer Palace in Ukraine to discuss their post-victorious plans to deal with the former axis powers, they managed – or at least appeared – to get on rather well on a personal level, even if their respective political beliefs clashed alarmingly. While on the surface the façade of friendliness may have seemed genuine, behind the scenes tensions were already mounting. While the three leaders agreed that it was in their mutual interests to cooperate against the Nazis, there were arguments about what the fascist regimes forcefully installed across Europe should be replaced by. There appeared to be a consensus towards allowing free elections and democratic governments, but this conflicted with Stalin’s need to secure the USSR against future attacks from the West (having lost well over 20 million as direct casualties of the Nazi invasion), and his resultant desire for a Soviet sphere of influence in the area from the eastern borders of Germany to the western borders of the Ukranian and Byelorussian SSRs. There was also the issue of how to manage Germany itself, once the Nazi regime was destroyed. Stalin wanted to punish the Germans and thrust socialism upon them, whereas Churchill and Roosevelt wanted to recover the country quickly so as to avoid the mistakes of Versailles. Eventually they agreed to divide the country between Britain, France, the USA and the Soviets, but the fate of Eastern Europe remained a grey area.

The Yalta Conference, for all its faults, was a fairly smooth affair compared to the one at Potsdam. Overall, besides a great deal of petty teasing between Churchill and Stalin, there had been little hostility over the political differences between the superpowers. At Potsdam, however, the tension was much greater. Partly this was due to a change in leadership: Stalin remained, as his leadership was undisputed in the Soviet Union, but the dead Roosevelt had been replaced by the more hard-line anti-communist Harry Truman, and partway through the British Labour Party came to power, and the Conservative Winston Churchill was replaced by Clement Attlee. This meant that a very different relationship now existed between the tops of the three powers. Also, without the common enemy of Hitler to fight against, it became harder for the three to look past their differences. Ultimately, the second conference achieved very little beyond finalise the divisions of Germany. The importance of this is that the USA and the Soviet Union had previously been separated by the vast expanse of the North Atlantic, and the nations of central/western Europe (the Bering Straight receiving surprisingly little attention). Recently, they had also had the common enemy space of Nazi-occupied territory to expand into. Now, however, the division of Europe and in particular Berlin had brought the worlds of capitalism and communism directly against one another, and so war seemed far more likely.

The first signs of conflict between the Grand Alliance appeared almost immediately, as the USA neglected prior to Potsdam to mention the development of the A-bombs used to defeat Imperial Japan. Stalin believed that Truman would be planning to use such weapons to make demands of the Soviet Union (which indeed he was). This saw the start of the nuclear arms race that would dominate the minds – and budgets – of much of the world for decades to come. The second sign of distrust was in the slow but sure build-up of satellite territories on either side of Europe. In Albania, the communists established instant domination, while Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Hungary were taken over by communist parties after brief reigns of left wing coalitions. By the end of the 1940s, everywhere east of Germany (bar Greece and Yugoslavia) was under Kremlin control. The Americans responded in a more subtle, but equally devious way: bribing shattered nations to remain capitalist. Though this was officially to help impoverished countries recover from the war, Stalin realised it was an attempt to turn the west into America’s own sphere of influence.

The result of this was that almost the entire continent was split between the American and Soviet power camps. Each side wanted to destroy the other, but neither side was willing to actually risk total war – especially once the power of the atom bomb was known. Naturally, the focal point of this pressure was in Berlin where, deep inside the Soviet Zone (or GDR), the western allies had developed a microcosm of the powerful symbol of western prosperity surrounded by communism, making it the point from which to advance the anti-socialist agenda (or the “testicles of the west” as Khruschev would later put it). In 1948 Stalin decided he could put up with such a dangerous nuisance no longer and blockaded all of Berlin’s connections to West Germany, hoping to stem the flow of disproportionately valuable individuals from the dilapidated Soviet Zone towards the apparently more prosperous West. Ideally, the west Berliners would have given up their ties to the USA, and turned to the USSR instead, but in fact America responded with continual airlifting of supplies for nearly a year, forcing Stalin to eventually give in. By this point, though, it was clear that both sides had made powerful enemies.

Overall, the prime cause of the Cold War was the convergence of the two different worlds – capitalism and communism – along the centre of Europe. The closeness of the Eastern and Western blocks forced citizens of both to truly interact for the first time, and so the formerly mysterious workings of the twos systems were finally laid bare. Unfortunately, these two ways of life proved incapable of peacefully coexisting, and so military tension was inevitable. The Cold War was, in essence, the product of the mutual drive between the Soviets and Americans to enforce their respective ways of life across a great many smaller countries, each attempting to win the approval of their client nations and prove that their economic system was superior. When expansion space ran out, it was inevitable that the two superpowers would try to oust one another’s grip. Originally, the political divisions of Europe were meant only to act as temporary measures after the Second World War, but the threat of Mutually Assured Destruction by nuclear bombs and the impossibility of reconciling the two ideologies ensured that tensions would remain high for a long time to come.

-

Crash Protection on Beagle 2

Exploring the physics behind the crash protection, and explaining why it failed.

Beagle 2, named after Charles Darwin’s HMS Beagle, was a British space probe, launched in 2003, which was intended to land and conduct scans on the surface of Mars in the hope of discovering signs of life. The mission failed when contact was lost and the spacecraft was thought to have either crashed or burned up in Mars’ atmosphere.

The Beagle 2 lander was a dome shaped object which was meant to safely land on the surface of Mars and then open out to deploy various pieces of equipment attached, including a UHF antenna, several solar panels and a robotic arm. To ensure that the craft made soft touch-down, it was equipped with a set of parachutes meant to deploy a set time after entering the Martian atmosphere.

In the original plan, Beagle 2 was to be released from the Mars Express Orbiter and fired towards Mars on December 19th. By Christmas Day, it was expected to have reached the threshold of the atmosphere. At this time, the Beagle would be travelling at a velocity of more than 20000km/h and thus could not land without being destroyed. To slow the descent, parachutes would be opened when the craft reached an altitude of 200m. To save on development costs, the parachute designs were replicated from the Huygens probe, then being carried towards Saturn. The parachutes would reduce the descent velocity of the lander, but would not guarantee a soft landing, so the surfaces of the lander was equipped with large airbags.

Whereas car airbags fire inside the capsule while allowing the outside to crumble, Beagle 2’s airbags would inflate around the outside and form a large cushion of air around the bottom of the craft to absorb the impact. The bags would deflate upon landing, allowing the craft to open. Helping this would be the gravitational field strength of Mars, which is only 3.7N/kg, compared to 10N/kg on Earth. The lander’s weight would therefore be reduced and thus the crash forces substantially lessened.

In reality, however, it is not known is the Beagle 2 ever landed at all, as the craft was never rediscovered after contact was lost. Subsequent investigations have come up with several explanations for what may have happened. Most such theories relate to the airbags and parachutes deploying at the wrong time. Whereas the ideal design would have included acceleration sensors which would deflate the airbags when the craft came to a standstill, ESA (lacking the resources if an equivalent NASA mission) instead resorted to a less expensive timer, with an educated guess having been made at when the touchdown would take place. Had the timer finished too early, the airbags would have been rendered ineffective at cushioning Beagle 2, which might thus have been destroyed in the crash. Another theory suggests that the parachutes (whose strap was reduced to save weight) may have entangled the probe and prevented it from opening, with the airbags causing the fast moving object to bounce back up to the inside of the chute. Finally, there is a theory that a programming error may simply have sent the lander off course so that it missed Mars entirely (which is possible, as a minor coding problem at NASA once caused the Mariner 1 spacecraft to be destroyed shortly after launch). The real story of Beagle 2’s loss may never truly be known.

Sources: wikipedia.org; Beagle 2 Mission Report, University of Leicester; dynalook.com

-

Circulatory Systems of Fish and Mammals

In both fish and mammals, respiration requires oxygenated blood to be pumped around the body through the circulatory system, powered by the heart, which draws in deoxygenated blood to add the necessary oxygen, then pumps the result to the rest of the body.

The process, for a fish, involves deoxygenated blood travelling through veins to the heart and entering the single atrium through the sinus venosus (a cavity which exists in the human heart, but is only significant in the embryonic stages). The blood is then forced into the ventricle (again, singular), from which it is pumped out into the large tube known as the bulbus arteriosus, which connects to the aorta. The aorta then carries the blood to the gills where it is replenished with oxygen and relieved of waste gases.

The newly oxygenated blood is then distributed to the body cells via the fish’ arteries, before veins carry the now depleted blood back to the heart.

The mammalian circulatory system is similar in that both involve blood passing through the heart by muscular contraction of each section to force it through the relevant valve into the next, followed by oxygenation in their respective animals’ points of gas exchange. Where the two systems differ is in the time between blood receiving oxygen at the gills/lungs and it delivering the oxygen to the respiring body cells.

In the single circulatory system of a fish, the oxygenated blood travels directly from the gills to the body. Mammals, however, have a double circulatory system, meaning that blood is returned to the heart before distribution. After blood has departed from the right ventricle and received oxygen at the lungs, it is pumped into the separate left atrium of the heart via the pulmonary vein and then it is forced into the left ventricle, which pumps it around the body to arrive at the right atrium again. The reason for the difference is that fish can exchange gas from many points on their bodies, thanks to gills, whereas mammals’ lungs provide only one point of exchange, so a more efficient setup is needed to keep the system working effectively.

-

The Purpose of Hibernation in Mammals

A description of the changes in a mammal’s body from the start to the end.

Hibernation is a process by which animals enter a state of inactivity for long periods of time, usually during colder seasons, so as to conserve energy during times in which food may be unavailable.

In times when food sources become scarce, an animal may be searching for their next meal for most of their waking hours, and thus expending more energy than they would be able to take in from whatever food they might eventually find. Since this inefficient way of survival would ultimately lead to starvation, some mammals have evolved instead to sleep through the harsher periods, with their internal processes slowing to a minimum to reduce the energy demand.

Prior to settling down to hibernate, the animal will consume far more food than they would normally. This builds up a large store of fat which will fuel what little activity takes place during hibernation and prevent muscle tissue from being consumed.

When the animal finally begins to hibernate, certain physiological changes take place which vary between different mammals. For bears, the body is able to internally recycle it own waste products, so that the bear need not feed or excrete. Rodents, meanwhile, experience brief periods of a return to higher body temperature in between long stretches of dormancy.

The general pattern for hibernation is that, as the body shuts down, it adjusts so that the body temperature is far lower than normal (from around 310K to 277K). The advantage of running a lower core body temperature is that less energy is expended to produce heat, and thus the fat stores last for longer. Breathing and heartbeat then slow down to a minimum, leaving the body effectively ticking over so that, from outside, it may appear almost dead. Most mammals would remain in this state for months, but others – those which cannot store large amounts of fat – will awake periodically to feed on food stores in its nesting place before resting again.

The end of hibernation, if not automatic, is normally triggered by the return to a higher external temperature. When the environment becomes warmer, the hibernator senses the change and begins to re-animate. The core body temperature will rise to normal waking levels, and bodily functions will speed up again until the animal is fully awake. Mammals who engage in torpor, such as bears, can become active again relatively quickly, whereas “deep” hibernators may take days to fully regain consciousness. Re-activating the body burns a large portion of the fat reserves (to generate enough heat), so animals which are aroused too early may be unable to survive for the rest of the hibernation period.

-

Passive Safety Features

An explanation of what they are and how they work.Passive car safety features are devices which, in the event of a car crash, automatically deploy to protect the vehicle’s occupants. “Passive” refers in this instance to the driver. Unlike “Active” safety features – such as brakes – which require the driver to work to prevent an accident, passive safety features require no deliberate input by the occupants and remain dormant until the moment of the actual crash.

Passive safety features include crumple zones, airbags, seatbelt pretensioners and safety cells (reinforced body shells).

Crumple zones are areas of the car which are designed to deliberately deform when the car collides with a heavy object. The purpose of this is to absorb some of the energy in the collision, so that the extreme forces of the crash are not fatally transferred to the occupants. The force of a crash is determined by a car’s deceleration during the collision. If the entire area hit is rigid, the deceleration will be very sudden, and so the momentum of the car will be transferred to those inside it, killing them. If, however, a softer, crushable buffer zone is in place, the energy will be transferred to the crumpling of that area, reducing the rate of deceleration inside the car.

Airbags work on much the same principles, but applied to the occupants. During a crash, the people inside a car are thrown forward relative to the cabin as the rest of the car decelerates around them. When their bodies hit the frame of the car, their internal organs collide with their ribcage, puncturing both and causing death. The cushion of air again acts as a buffer zone to spread the victim’s deceleration over a larger space and time, so that velocity is greatly reduced, and so the internal impact on the ribcage is not as harsh. Modern airbags are controlled by sensors which determine the severity of the crash forces, and so the bags are fired at the precise time (to the nearest hundred milliseconds) for the optimum effect. Too late and they would be useless, too early and they may cause more damage than they prevent.

Pyrotechnic seatbelt pretensioners are used to restrain the occupants upon impact, and hold them in place so that the airbags may work correctly. If there is no restraint, the driver/passenger’s body will be flung forward, with the head violently striking the dashboard. Instead, pyrotechnic charges fire upon impact to suck the belt inwards, clamping the wearer flat against the seat so that they are in the correct position when the airbag deploys.

Government statistics report that the use of seatbelts saves around 2200 lives every year in the UK, while around 26000 lives of US drivers have been saved by airbags every year since their introduction.

Sources: caradvice.com; howstuffworks.com; holden.com; wikipedia.org; airbagcentre.com; doeni.gov.uk

-

Was Stalin a Disaster for the USSR?

An essay in response to the titular question.

Throughout most of Josef Stalin’s reign as leader of the Soviet Union, there was no doubt in the minds of most westerners that the man, and the country he represented, were pure evil. However, Stalin could usually shield himself from this behind the Iron Curtain, where the population were forced to worship his Cult of Personality. To some, though, Stalin was not only an enemy of the free world, but also of his own people. Was Stalin the destroyer of his own motherland?

Certainly, it is clear that Stalin cared little about the wellbeing of the people under him. In his handling of the collectivisation process, he showed no concern for the fact that thirteen million peasants starved to death during the famine he had caused. Noteworthy is that the USSR continued to export food abroad, and even leave large quantities of grain to rot directly beside the starving farmers. This shows that he placed little value on human lives, even in enormous numbers. He once pointed out to Winston Churchill: “One death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic.” and not only was he willing to let the masses perish by negligence, but he actively destroyed a great many of his own, too.

The Great Purges, in which anyone who even once so much as made a joke at the expense of the communists was arrested, imprisoned, killed and erased from history devastated the Soviet Union. An important thing to remember here is that, while Lenin and Trotsky before him has certainly been ruthless with their enemies, they had been fighting genuine threats in the name of advancing their ideals. Stalin, however, seemed primarily concerned with consolidating his own position. This is evident in the roles of those he purged. Leon Trotsky, the brilliant strategist, commander and motivator who had single-handedly built up the Red Army from the remains of the Tsar’s Imperial Russian Army and whoever else could be found in Petrograd, was unceremoniously turfed out of Russia and eventually murdered. In the Red Army itself, 90% of the Generals were purged. This meant that the USSR was a weak target for the Nazis and, though the Soviets eventually turned the tables on Hitler, destroying all of the German forces east of Berlin, it was not until they had suffered a huge blow. Stalin also removed old political rivals such as Kamenev, Zinoviev and Bukharin. None were capitalists. All had been part of the original Bolshevik party, and all had helped the revolution. But while they were communists, socialists and Marxist-Leninists, they were not Stalinists, and so they had to die. Even at a ground level, Stalin persecuted artists and intellectuals who seemed too critical of his regime. Ultimately this had the effect of transforming the glorious new world back into the dictatorship it had been under the Romanovs. What all of this proves is that Stalin was easily willing and able to destroy all that the Revolution had aimed for simply to protect his own power. He was not working towards a free and equal society, but an enormous temple to himself, in which he could rule supreme. His aims to industrialise the Union were done purely to secure Stalin against his enemies. The result was far from what Marx would have wanted.

There were, however, some positive aspects to Stalin’s leadership. Thanks to the Five-Year-Plans, the USSR was finally brought up to the industrial level of Western Europe – if for the aforementioned wrong reasons – and began to modernise the Union by making education and medicine available to all his subjects. He also allowed everyone in the USSR a job capable of sustaining their needs (just). Furthermore, he not only repelled the German invasion, but added extra territory to the USSR by taking over much of Eastern Europe up to West Germany, creating an enlarged Soviet sphere of influence and advancing socialism further throughout the world. He also succeeded somewhat in terms of the egalitarian “worker’s paradise” as, although the overall standard of living remained considerably lower than in the West, there were far fewer cases of extreme poverty. For this, he deserves some credit.

Even so the fact remains that after Stalin passed away, his reputation as a demigod did not last long. Just as Uncle Joe had sought to remove his enemies from time as well as space, his replacement Nikita S. Khrushchev began too a programme of “De-Stalinisation” in which the former dictator was himself purged from history. Stalinist ideologies were discouraged, references to him in the national anthem were removed. In 1956, Khrushchev publicly attacked the Cult of Personality around Stalin, and encouraged people to distance communism from the man as far as possible. Stalin, it seemed, had quickly ceased to be a hero of the revolution and become instead a great embarrassment to the entire country. While it was never possible to completely unperson such an important figure, Stalin was not remembered as fondly as his contemporary cult might have suggested. Certainly, he never enjoyed anything like the posthumous fame with which Vladimir Lenin had been showered after his death.

Overall, it appears that, despite some noteworthy achievements, the quarter-century which the USSR suffered under the Stalinist regime was not the Soviet Union’s finest era. Stalin, for all his praise and worship, has been best remembered as a totalitarian dictator who massacred millions of his own people and destroyed freedom across Eurasia for decades. This reputation sadly tainted that of the entire USSR and by extension communism as a whole. Had a less ruthless leader taken his place, the Soviet Union might have averted its transformation into a police state and instead developed towards the perfect society that Karl Marx had written about, in which all were free and equal, not some more equal than others. Perhaps the original aims of the Bolshevik revolution would have been fulfilled, but now we shall never know.

-

The Falling Penny Myth

Why it is impossible for a dropped penny to kill someone.

There are many variations of the story in which a penny is dropped from the top of a very tall building (such as the Empire State) and plummets to ground level, where it fatally strikes the head of a pedestrian below.

In fact, the falling penny would be far less harmful than most people imagine. Because the mass of a penny is around 3.5 grams (depending on the currency), the weight pulling it downwards is only 0.035N.

If dropped from a great height in a vacuum, the coin would accelerate downwards at 9.8m/s^2 until it hit the ground. By this point, if the height used was the Empire State (443m), it would be falling at over 300kph (83.3m/s). This would indeed be enough to kill an unprotected victim.

However, in reality, the friction of the coin against the air would force it to descend at a far lesser speed. Because the penny has (for its mass) a proportionally large flat surface area, it will experience a large aerodynamic drag force. Depending on wind conditions (and the type of coin used), the drag could result in a terminal velocity of only around 10m/s, which would be insufficient even to cause mild pain for more than a few seconds to anyone hit by it.

Sources: scientificamerican.com; howeverythingworks.org; science.howstuffworks.com

-

Stalin CPSU Leadership

A one-page reply to the statement “Stalin won leadership of the Communist Party due to his own cleverness”

A one-page reply to the statement “Stalin won leadership of the Communist Party due to his own cleverness”It is undoubtedly true that Stalin possessed a great cunning. He rose through the ranks of the Bolshevik Party (from General Secretary to undisputed leader of the Soviet Union in under a decade) using a series of devious but ingenious tricks. Though not especially intelligent or eloquent compared to Trotsky, Lenin or Bukharin, he certainly knew how to manipulate large groups of people. He used an apparently unimportant position to slowly build up support in the Communist Party ranks by populating them solely with his own followers, and then used what could be considered mind control techniques to turn the Soviet people against his enemies. By removing party candidates who might have become Trotskyites, and then turning the remainder against each other, he managed to destroy all potential opposition without having to directly challenge them all. The important part of his plan was to play on the people’s common fears about Leon Trotsky. Many at the time believed that Trotsky was too powerful, and that he could become an extremist, totalitarian dictator, thus turning them to pull away from him and vote for Stalin instead (ironically). By use of the propaganda tricks, revisionist history and exploitation of fear which would later become synonymous with his era, Stalin could encourage a frenzy of hatred against his political enemies. Also, with his tricking of Trotsky at Lenin’s funeral, and his cashing in on the cult of Lenin in general, he made himself appear to be Lenin’s closest friend (or rather the Soviet Messiah), and thus elevate himself to divine status.

There is, however, some weight to the argument that Stalin’s rise to power was not purely down to his own brilliance. Looking at the situation prior to his coup, we can see that he was blessed with several strokes of luck. Foremost among these is the fact that Lenin appointed him General Secretary to begin with. Clearly, the old Bolsheviks overlooked the power of this position and underestimated Josef’s lust for power. He was also lucky that Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev were so quick to quarrel with each other, thus providing an opportunity for him to attack. He also had a very narrow escape when the other party members decided not to publish Lenin’s last will and testament, for though it also criticised his enemies (including Trotsky), it was he of whom Lenin appeared to be most cautious.

Overall, it is true that Stalin was deviously cunning and did possess some tactical brilliance, but it was only due to several lucky breaks that he was ever able to put it to use.

-

The Cost of Clienthood

An account of the difficulties of being a client, according to Martial.

An account of the difficulties of being a client, according to Martial.Being a client during the Roman era would give a man financial support, and assistance, but there were many obligations which had to be fulfilled, and often a patron would want to make you well aware of your place.

Martial wrote several epigrams about the struggle of being a client, and the ways in which a patron could take advantage of you.

In Patrons and Clients: 3.60, Martial describes the inequality of the food given to patrons and clients. At a meal with Ponticus, Martial sucks mussels and is fed pig fungi, bream and a suspicious magpie. Martial feels disconnected from his patron, who receives oysters, mushrooms and a golden turtle dove.

As detailed in 5.22, attending the salutatio with Paulus requires Martial to walk away from the Tiburtine pillar to the Esquiline, including steep slopes, arid stone steps, and cavalcades of mules with marble blocks. He arrives, soaked and exhausted, to be told that Paulus is not in his house, making the entire charade pointless.

Another patron, Caecilianus, fines Martial one hundred quarters simply for not addressing him as “my lord”. (6.88)

Even on a good day, a client’s wages were disappointing: Martial’s daily wage of one hundred lead coins can be trumped in one hour by Scorpus, a champion charioteer, who earns fifteen large sacks of gold. Martial, feeling unappreciated, longs for rest.

One peculiar case is a patron name Maximus: (2.18) shows him pandering to another, even richer man. Martial realises he is a client of a client, and that Maximus may not be so different to him after all.