-

Is it irrational to believe in a god we cannot see?

An essay on the logic of theism and deism.

An essay on the logic of theism and deism.Some would argue straight away that this is an invalid question. Of course we can see God! He created the earth and the stars, he even created you! Others would claim that we can only see God when he wants to be seen, and that otherwise he must remain hidden from the world. The fact is that God’s visibility will depend on who is looking.

In ancient times, when man had barely left the primate stage, there were many questions that were seemingly impossible to answer. Nobody knew why the sky was blue, or why the moon appeared at night. Prior to this point, we would never have thought about such matters. All that was important to us would have been to hunt, eat and mate. Now, however, we had begun to develop sentience. For the first time, we were able to ask questions about our very existence. Unfortunately, the answers did not come easily. Cavemen would have had no concept of water evaporating, or of light refracting in the sky. To our ancestors, there seems to be no possible answer that humans could understand. It must have come from someone or something higher, something more advanced, more intelligent than we could ever imagine. It must have come from God. Throughout the ancient world, primitive tribes developed ideas about the various deities who watched over the earth. These ideas then became “truth”, and so society was built upon rituals and worships in order to please the gods.

Were they right to live in this way? Were all of the ceremonies, offerings and sacrifices truly necessary? Today we would not think so. Today we look at Egyptian burials, with the bodies embalmed and the organs placed into canopic jars, KNOWING that it was all in vain. Nobody today would blame Poseidon for a stormy sea, or ask Thor for rain. When we look today at ancient beliefs, we know that they were lies.

Yet today, many of us still believe in Jesus, Allah, Vishnu, Ganesh, Buddha, and many others. I find it quite odd that we still worship these deities, even though we are able to dismiss the gods of the ancient world, without a moment’s consideration, as mere superstitions. However, before I delve into the reasons that people choose to be religious, I wish to first discuss some of the details concerning the nature of the Almighty.

The topic in which I am writing this essay is “The Nature of God”. From this we can extrapolate one point: God has a nature. This is a reasonable assumption to make, since anything outside of nature cannot exist. However, God’s nature has never been precisely defined. If we assume that he is made of matter and/or energy (as all things with a nature must be), then he is bound by the universal laws of physics. It is conceivable that such a being could create a planet, but inconceivable that such a being could create the universe itself, because such a being would have to, at first, be outside the universe (since you cannot invent what already exists). This is not possible however, since the universe is a synonym for all of existence and nature, so if God created existence, then God cannot exist. If he does exist, he cannot have created the universe, and he can only be an alien, not a god. Through this we can see that no deity worthy of worship may actually exist.

Many theists and deists might claim that it is foolish to try to work out the nature of god through human logic, because the Lord exists outside of what humans can conceive of. Firstly, this is a mere cop-out designed to steer away the argument and, secondly, it rests on an unfalsifiable hypothesis. For example, I could suggest that there was an elephant behind you, watching you browse this website. If you turn around, you will see nothing, because the elephant is invisible. It is also silent, intangible and odourless. I, however, know that the elephant is there because it has appeared to men many times, and spoken to me telepathically. Of course, you cannot see or otherwise sense him, but that is only because you do not believe. You must start to believe now, because the elephant has promised to me that he will re-enter our universe and trample you to death if you copy and paste this essay.

Obviously, this is nonsense. It is true you cannot disprove the existence of the invisible elephant, because I have produced an unfalsifiable hypothesis, but by the same token I cannot prove the elephant exists, either. Unless the elephant were to actually appear in a provable form, we have no reason to assume that such a creature exists and thus no reason to believe in it.

If we translate this metaphor back into religious terms, then we have no reason to believe in any god either. Certainly, there have been countless books written about him/her/it/them, but these were all written thousands of years ago by unconfirmed authors, and then translated (often rather haphazardly) into thousands of languages. This, and the fact that they include things which we know are not true (the great flood, talking snakes and “miracles” which can be outdone by modern magicians), means that they are not reliable sources of information. We therefore have little proof of god’s existence beyond shaky stories from so-called witnesses. For all we know there could be thousands of invisible, intangible, undetectable deities (known henceforth as UFH gods), but without solid evidence of their existence, we have no reason to believe in them, let alone worship them.

Why then do people still follow religions? Is it because they have had it indoctrinated into them during early childhood (consult Richard Dawkins)? Is it because they cannot understand the world not having a creator? Or is it out of fear…

A major reason for people following a particular religion is that they fear going to hell (or its equivalent in other faiths). Indeed many devout believers in a particular religion (especially fundamentalists) are willing to go to great lengths (even so far as murder) just to ensure that they please their god, and thus will be “saved”. Appropriately, they preach that anybody who does not comply with their religion will “Burn In Hell!”. Though these people make up a small portion of each religion, there are many people from other variants of the faith who worship because they fear damnation. Yet even if you believe that your religion is right, you have no way of guaranteeing the afterlife you want, because the criteria for entry into the kingdom of God are never explained. In the Holy Bible, for instance, Jesus says that in order to be saved, one must;

-

Simply love God, and thy neighbour (Luke 10: 25-28)

-

Sell all of your possessions (Luke 18: 18-22)

-

Obey the commandments (various)

-

Hate everything about your life – including everyone you know (Luke 14: 26-33)

-

Drink the blood and eat the body of Christ (John 6: 53-54)

As you can see, Jesus gives a different set of instructions every time, some of which are reasonable, some are idiotic, and the rest blatantly contradict each other: How, exactly, are you supposed to love everyone and everything, yet also hate it. Also, why is it necessary to sell all your possessions? This jarring lack of consistency shows that Jesus (or, indeed, whoever was posing as Christ) had no idea what he was talking about, much like when criminals try to concoct alibis but cannot keep their stories straight. If the Bible is to be taken as perfect truth, then access to heaven is impossible.

In fact, access to a good afterlife is worse than impossible, because, even if there is a God, it would probably not be Yahweh: It would most likely be one of the UFH gods. Since we know nothing about them, we have no idea as to what the divine criteria might be. For all we know, God might want us to send our entire lives dressed as chickens. In fact, because there are potentially infinite UFH gods, the chance of picking the right one and correctly worshipping it are – mathematically speaking- zero, and if the one true UFH god is anywhere near as petty as Yahweh or Allah; we will surely have displeased him and will be sent to Hell for all eternity.

To conclude: It is deeply irrational to believe in a god we cannot see, because not only can we not see it, but we also cannot taste, hear, touch or smell it, and because, if there does happen to be some sort of god,

WE ARE ALL DAMNED!!

-

-

The Message of Ozymandias

An interpretation of what Percy Bysshe Shelley was trying to say

The poem seems to depict Ozymandias as a forgotten dictator, who once considered himself to be an almighty king, but whose empire has long since collapsed. The sonnet describes a “half-sunk, shattered visage”, inscribed with “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” this is clearly an attempt by the sculptor to ridicule Ozymandias in front of future generations, by drawing attention to how all his monuments are now wrecks. It also exposes the king’s vanity, as he supposedly believed that the statues described would have lasted for the rest of time, as testament to the glorious might of Ozymandias! Instead, the writing lays bare his foolish short-sightedness, almost parodying him as it strips the king’s legacy of all dignity and honour.

The exact message of “Ozymandias” is difficult to precisely articulate, but it could be said that, no matter how great and powerful you consider yourself to be, time will always tell how you truly are.

-

Classifying the Platypus

A verdict on which group of vertebrates it should be placed into, including positive and negative reasons.

Though the platypus’s bizarre construction can often lead to questions as to its classification, it is officially regarded as a mammal.

The platypus has many properties associated with mammals: They have fur covering their bodies; they feed their young through the mammary glands, and are warm blooded. Some features of the platypus, however, suggest a rather different origin.

The most controversial aspect of the platypus is the fact that it lays eggs. Though every other class of vertebrate lays eggs, mammals are normally born live. Other attributes, such as the duck-like snout, the webbed feet and claws initially led scientists to believe that the animal had been faked!

It could be argued that the platypus is an amphibian. They normally live both in and out of water, and must submerge to lay their eggs, much like amphibians. However, amphibians cannot have fur, are cold-blooded, and begin life as tadpoles or larva before developing into their adult form. None of these features applies to a platypus.

Overall, the majority of a platypus’s characteristics point to it being a mammal, with its egg-born status being something of an anomaly. The platypus therefore has a unique classification: A monotreme. The only other animal with this identity is the echidna.

-

Victorian Health

A short essay describing the level of hygiene which the Victorian working classes experienced, discussing the reasons for health measures being so poor.

A short essay describing the level of hygiene which the Victorian working classes experienced, discussing the reasons for health measures being so poor.When people discuss the Victorian era, they talk about the British Empire, Queen Victoria and the many inventions spawned during the Industrial Revolution. But another subject frequently mentioned is public health, or rather the lack of it. The Victorian poor famously lived in poverty, hunger and filth. Families were squeezed into disease ridden terraces where clean water and personal space were too costly a privilege. Many died of hunger and disease in yards which were constantly flooded with stinking water. Many have often wondered how urban life could possibly have become such a nightmare, and why it took so long for any serious effort to be made in order to repair the situation. The answer is simple: Nobody who mattered cared, and nobody who cared mattered.

The problem began early in the 1800s, when the Industrial Revolution forced changes to the way that people lived and worked: Instead of local trade and agriculture, industry and technology had become the focus of employment. A large portion of the less wealthy population drifted from farms and villages into the rapidly expanding cities. Fitting them all in would require the building firms to put together their finest brains to come up with a then-modern miracle of compact design and low-cost construction. But why waste all that time, money and effort trying to accommodate a bunch of peasants who, after all, did not really matter. Surely it would be far easier to just pack them all into whatever took the least money to put up, regardless of whether or not the resulting lifestyles were actually suitable for the lowly families who were forced to endure them. The outcome of this decision was that every working class house in the big cities was a cramped, under-equipped and poorly constructed wreck. Living in a confined and unsanitary area such as this was perfect for attracting filth, pestilence and an early pauper’s grave.

The main issue with living in a yard such as this was what to do with household waste. With no sewers, recycling or even dumping ground, rainwater, industrial by-products, faeces and probably even dead animals (or children) were able to accumulate over time, leading to numerous outbreaks of disease and infection form contaminated food and water sources. Again, the reason for this was that in the eyes of the landlords and town councils, poor labourers did not matter. As a result, duties such as repairing houses, supplying clean water and extracting the waste from local cesspits were often neglected, with authorities electing to spend the money on themselves instead (Obviously, the councils and governments of today would never delay answering people’s urgent needs, use tax money to buy goods for themselves, or commission housing on unsafe land.). This is perhaps the strongest factor in the health plunge: the poor had no real access to any sort of medical aid and, as a result, lived in a world of sickness.

There were many different ways in which the Victorian underworld could kill you. You could die of Cholera; a bacterial infection of the small intestine which could turn your skin blue while causing intense vomiting and diarrhoea. There was also tuberculosis, which attacks the lungs as and causes victims to cough up blood, as well as typhoid (which, if untreated can ultimately cause a haemorrhaging of the intestines) and scarlet fever (causing a large rash, peeling skin, and swelling of the tonsils). Throughout the nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands died from numerous outbreaks of these illnesses. The constant threat of sickness was largely due to a lack of knowledge about the spreading of disease. It has taken centuries for scientists and doctors to learn (and society to accept) that illnesses were spread by viruses and bacteria rather than foul odours or the Wrath of God. Even when the development of medicines had begun, there was still virtually no chance of the message getting through to those who needed help. Yet again, making the necessary changes would be too expensive and nobody wanted to cough up for the schemes because the worst affected were the poor, and the poor didn’t matter.

In conclusion: The catastrophic waves of disease in Victorian towns were brought about because no serious measures were taken to prevent them. During this era, the rich had no sympathy for the lower classes, and did not care about their heath at all. This led to decades of neglect and suffering for the miners, factory workers, and child labourers at the time, who were simply to suffer alone in a world which, retrospectively, seems almost purposefully designed to kill the unwashed masses.

To summarise, this is my opinion of why health in Victorian times was so bad:

Life costs, and peasants weren’t worth paying for!

-

Comparison of British India and Hong Kong

A comparison of how the two places fared under British colonial governance.

A comparison of how the two places fared under British colonial governance.British Control of India

In 1583, Queen Elizabeth I had a vessel called the Tyger sent towards India, with the task of finding trade opportunities to exploit. By 1614, and office in Bombay (Mumbai) had been opened by the British East India Company (a trading organization for the Empire).

The primary reason for taking control of India was for textile trade (such as rare cotton), but the British also developed a fondness for Indian-grown tea leaves.

While under the control of the British East India Company, many Indian citizens were treated as business opportunities and slave labour. The British would manipulate the “Kings” of various warring groups into destroying each other, so that the remaining wealth and power of both factions could be absorbed into the Empire. When the British themselves needed to go into battle, Indian soldiers would often be recruited, but rarely given respectable ranks or positions in the military. As well as exploiting India, the Empire also nearly crushed its economy, Indian cotton industries going out of business and the majority having to buy the much more expensive British cloth instead. There were, however, many benefits to British influence. With Britain leading the way in all matters of machinery and transport, India was quickly transformed. Railways were constructed all across the country to allow businessmen and haulage companies access to key areas. Schools, universities and factories also sprang up all around, transforming India into a far more modern country.

India eventually revolted against British control, and gained independence in the 1940s, but today many relics of the Empire still remain. There are still several recognisable British buildings, such as a huge memorial to Queen Victoria in Calcutta, and one of the most common cars on the urban roads is the Hindustan Ambassador, virtually identical to the Mark III Morris Oxford. Many tourists describe towns and cities in India as being “…like England back in the 1950s.”

British Control of Hong Kong

The British took control of Hong Kong to exploit the addiction to Opium held by many Chinese. Opium had been made illegal by the governing body of China, but the British traders were determined not to lose the opportunity to make money from the Chinese, and so forcibly seized control of Hong Kong in order to continue the business. In contrast to the Empire micromanaging most Indian affairs and attempting to convert people to Christianity, Hong Kong residents were free to practice their own religion, and were better respected than Indians. At the beginning of the British Rule, Hong Kong had only 1,500 residents, and fish was the main trading currency. By the mid-1840s, the population was soaring towards twenty thousand, with many foreign businesses setting up shop in what seemed like the perfect trading port.

Today, Hong Kong is a thriving city, with a population of over 7,000,000. Unlike in India, where the ghost of the Empire is still clearly present, the Chinese have replaced most of the old buildings in Hong Kong with brand new developments. Apart from a love of pets apparently adopted from the British, there is very little evidence that Queen Victoria was ever involved with the city’s development at all.

-

Caravans in Room 101

A speech explaining what I would send to Room 101 and why.

For exile to Room 101, I would strongly recommend the caravan. For years, the motorways of Britain have been clogged, every summer, Easter or bank holiday, with the persistently slow and wobbly menace that is the caravan. Some people may claim that these dingy plastic depression machines are “brilliant for getting out and seeing the countryside” or “a perfect little home form home”, when in fact they are neither. A caravan holiday consists of hitching up a massive block of flimsy plywood, pebble-dashed fiberglass and hideous plastic to the back of whichever car you can find that has a tow bar (rather than one which is fast, comfortable, reliable, efficient, practical or stylish), and ambling along many motorways and A-Roads at speeds of up to 35mph, while behind you, thousands of cars honk, beep and swerve as they try to get out of the traffic you have caused. When you eventually reach the campsite – a flat green field next to a road, just like you have in your own area- you must then park, unhitch the torture centre from the back of your 25-year –old Volvo, set up the gas, electric, and water tanks, then settle down inside the rolling Tupperware box. Then you can get used to “the wonderful world of camping”: Living in a house smaller than a garden shed, in a field where hundreds of other, equally foolish/misled families have also hitched up their own fibreglass depression chambers – although not nearly as depressing as yours, because they have a much bigger caravan with a wide-screen television and nicer-looking beds – and whose children are now running around screaming at this new stuff called “grass”. Then, when you need the toilet, you must squeeze into cordoned-off cubbyhole behind the 70’s velour sofa and defecate into yet another hateful plastic tub. At dinner, because the caravan will not have adequate room, facilities, or ventilation to let your parents cook dinner, you will have to go “t’ local pub” and wait for half an hour to get an overpriced version of something you could have microwaved in a packet. Then, when it is time for bed, the whole family must convert the sofas into submarine sized beds, and sleep together in the cramped, smelly, fiberglass depression machine. Even when it is time to go home, the misery persists, because you must pack away the flimsy deck chairs and plastic dinner sets back into the caravan; disconnect the water, gas and electric, then empty the camping toilet. How many of you seriously want to spend a holiday carrying a bucket of your own and several other people’s faeces to a disposal pit inside a wooden hut.

Not only is caravanning not good for your will to live, but it is not cost effective either; a new caravan will cost at least £10,000, and in this day and age, fuel costs will eat into your savings even more. Also, caravans are notorious for causing traffic jams on fast roads, as they are not allowed to exceed 50mph, and even at that speed the trailers can still wobble about dangerously (on sharp corners they can flip over if pulled too quickly). There are some people who argue that caravans are a good thing, and that they would not be able to cope without them, but this is simply not so; since most campsites already have washing and sanitary facilities, campers could easily switch to tents which, though equally horrid, can at least be folded up and placed in the car. Caravans are not necessary, and removing them will improve the world by and large.

-

From the Diary of Napoleon Bonaparte

An estimation of Napoleon’s diary entries before and after the Battle of Waterloo.

Mars-vingt, dans l’année de notreseigneur 1815

At last, I am in a position of supreme power. Today “King” Louis XVII has abandoned Paris, and I have taken control of the Capital of France. I have preached to the people that I would like a peaceful reign, but I am unsure as to whether the other countries will acknowledge that. I suspect that the British might want to eliminate me, and the Austrians, Prussians and Russians are likely to join them. I only hope I can make a good enough impression as a dictator, then they might stop wanting to come after me.

Aujourd’hui c’est le quinze juin, dans l’année de notre seigneur 1815

It has now been nearly three months to the day since I arrived in Paris, and now it is finally time for this final war to commence. The British, Russians, Austrians and Prussians have united against me. If their armies team up, and fight me as one, my forces will be overwhelmed. However, if I tackle them individually, I may stand a chance of defeating them, Today, I must make my first move; separating Wellington and Prince Blucher. They have planned to rendezvous the British and Prussian armies in Belgium soon. I am to march my own soldiers into the gap between them before the two nations can combine their forces. Tomorrow, I will take on the Prussian army down south. I must crush their troops, so that I may then regroup my full force and unleash it upon Wellington. At least by that point, half of the war will have been won. Until then, I can only pray for victory in Ligny.

Aujourd’hui c’est le seize juin, dans l’année de notre seigneur 1815

Today, I have been in luck, my army took on the Prussian army at Ligny and we have beaten them. After a glorious battle, the ground is red with Prussian blood, and those that survived have fled in terror. My men are too tired to pursue them now, so I will wait until tomorrow to send a search party. This will allow me to study their movements and tactics. Unfortunately, the only general available for this mission is Grouchy (least experienced of the lot), so I will have to give him a sizeable chunk of my men to fall back on should his brain fail him.

Aujourd’hui c’est le dix-sept juin, dans l’année de notre seigneur 1815

The time for battle is so nearly come, I know that I must engage Wellington within twenty-four hours in order to win this war. The pain of waiting is excruciating, but so is the pain from a rather different source: Haemorrhoid agony. I have enlisted a surgeon to treat my piles, but the effects of the treatment are taking a long time to work. Brushing that issue aside: I have dispatched thirty-three thousand soldiers to track down, scan and exterminate the retreating Prussians, because if they successfully team up with Wellington’s forces, I will be finished. If I am killed in action, then I only hope that this diary will survive, and preserve the brilliance of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Aujourd’hui c’est le dix-huit juin, dans l’année de notre seigneur 1815

Le matin

My soldiers are getting nervous, for some have been defeated by Wellington in Spain. They picture him as a great, conquering dark lord who will strike them with his wrath. I must convince them to stay strong, otherwise their broken nerves may cost me this fight.

L’après-midi

I was about to win this battle! I had Wellington cornered and crippled. But then those blasted Prussians arrived. Thirty-thousand reinforcements broke through the French lines and rescued Wellington from certain doom. Of course, Is should also be gaining just as many extra men, as I sent Grouchy with thirty-thousand plus troops to follow those Prussians. Yet the God-damned nitwit is nowhere to be seen! If General Grouchy does not come to my aid within the next few hours, I will be defeated! To hell with the Waterloo rain: If we had not been forced to delay our attack, the battle could have been won! By rights the drizzle should have been an advantage, since the British usually hurry inside when the rain begins. We could have obliterated them while they were sat down drinking their tea. Now it is likely that I will be forced to flee.

Le soir

I am wounded, humiliated and defeated. The British/Prussian cavalry charged through my own, and the French had to run for dear life. I am unlikely to survive now, and a comeback from Waterloo will be almost impossible. This therefore, is probably the last entry into my diary. I may be captured an executed, but my name will live on throughout history. Nobody will forget the legacy of the great Napoleon!

-

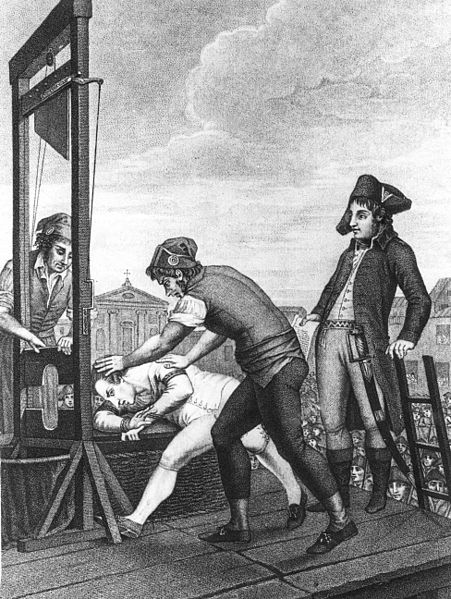

Robespierre Obituary

An obituary about revolutionary French lawyer Maximilien de Robespierre.

An obituary about revolutionary French lawyer Maximilien de Robespierre.Here lie the head and body, now separate, of Maximilien de Robespierre. This is a man who was once bold, kind and courageous. With no parents from his early teens onwards, he might have been destined to starvation, or to insanity and a life of crime, but instead he became a lawyer, and strove to the defence of those who could not afford to buy their way out of legal issues. After this, he became an even greater scourge of injustice. This he achieved by finding his way into the National Convention, where he supported the abolition of horrors such as the death penalty, and slavery. He was, for a time, a driving force behind the light of all that is good. But, alas, it could not last for he at first opposed the Terror, but then something about him changed and suddenly, the Terror was good! In his final years he began executing the French country folk, even his old friends! Now that the crisis is over, I am glad we have finally been able to silence him. He was once a soldier against wickedness and corruption, but he himself became evil and far too powerful for his own good. Eventually, he lost his head, so he had to lose his head. Perhaps now, in Heaven or Hell, his fiery passions may at last be damped.

-

Private Peaceful: Two Months Later

An extra chapter, to add to the end of Michael Morpurgo’s Private Peaceful, explaining how the family react to Charlie’s death.

The carriage clangs and rattles as we roll across the old Cranberry passage bridge. Outside, the sky is clear blue and the sun is shining bright, but the cold grip of the winter still clings to the leafless trees and damp, mud strewn grass. Normally the farmers would be working the fields, in preparation for planting the seeds, but now they are nowhere to be seen. Perhaps, like me, they were called off to battle, forced to trade their spades and pitchforks for grenades and rifles. I shudder as I think that, even now, as I sit on the train home, they might be huddled in a trench somewhere, listening to the shells exploding and the guns of the wipers blazing in the distance. All the great nations have poured so much into fighting battle after battle after battle, so many people, riches and resources have been lost that there now cannot be possibly be anything left worth fighting for.

I sink deeper and deeper into my memories about my career in the army. I remember pretending to be a twin in order to get in, I remember running laps with my gun held above my head because of vile, horrible wicked Hanley. I remember feeling seasick over the channel, the training camp at Etaples, when we caught the German naked after we stormed his trench. I remember meeting Anna at the Estaminet in Pop, and then I remember Charlie. Don’t think about it, Tommo, don’t keep going back there. But I can’t help it; no matter what I do to distract myself from it, my thoughts eventually lead me back to the firing squad, and to Charlie singing Oranges and Lemons in defiance as the bullets flew towards him. How he ended up sprawled across the ground, stone dead. How Hanley had my brother court martialled for cowardice and disobeying orders, even though Charlie clearly knew better than the sergeant (who lost most of the group because of his idiocy). I keep thinking how, if death is the punishment for disobeying orders, there must surely be a death penalty for getting your company pointlessly slaughtered.

Then I wonder what I would have done in Charlie’s place; if I would have gone with the sergeant, and died in the mud, knowing I had given my life for nothing, or if I would have said no, and then been through an unfair court martial culminating in me being shot by the firing squad. What really annoys me, though, is the timing of Sergeant Hanley’s death. If Fritz had just aimed a little straighter, then Hanley would not have been able to punish one of his group for his own stupidity. Instead he managed to hold on ‘til he had done the deed before finally sinking into the fiery depths of hell, where I am sure he will be most welcome. Eventually, I manage to pull myself out of this horrible mental loop and focus on a happier subject, like meeting little Tommo for the first time.

*

With a hiss of steam and a loud whistle, the train comes to a standstill, and through the clouds of steam, Eggesford Junction Station comes into view. I have been told in advance that the family cannot be here to meet me, as Molly is still working and mother is tending to Big Joe. Apparently Big Joe fell into a river a week ago and caught a dreadful cold. The colonel had tried to wallop him, but Mother would not let anyone near him until he had calmed down a little.

I wonder to myself how Mother always managed to stand up to him, to protect Charlie and me no matter what the circumstances. Perhaps Molly will one day be in the same situation with little Tommo, her son, my nephew. Perhaps one day little Tommo will go poaching in the colonel’s river, or will get humbugs from a lost pilot. Maybe I’ll be there with him, “Uncle tom”, looking after the child like Charlie never can, acting as little Tommo’s father figure. But how would I know how to be a father? What example do I have to follow? One thing is for sure: I shall never let little Tommo near an unsafe tree. The crowds on and off the train push and babble as they swap places, meanwhile I slowly walk down the platform, ‘round the back of the station and down the road to the colonel’s estate. It is getting warmer now, the road ahead of me is bathed in a warm glow from the sun high above, and as the colours of the grass and the sky start to come out, I begin to feel at home once again.

*

After a stroll of about twenty minutes through the much-neglected countryside, at last I catch sight of the little cottage where I grew up. Despite the difference in the weather, and the lack of as many pretty flowers in the garden, it hasn’t changed one bit. I look through an upstairs window and see a figure gazing at me, it must be Mother, she realises I have seen her and she rushes down the stairs, out of the back door, frantically hurrying towards me.

“Tommo!” she cries “Oh, Tommo, my baby!”, and for a brief moment I wonder if she remembers which Tommo she is talking to. She meets me halfway down the hill and hugs me tighter than ever. I try to hug her back but have difficulty trying to wrap my arms around her while carrying a heavy suitcase. Together we walk towards the cottage, and she keeps asking me questions about the army, about the trenches, and Sergeant Hanley and

“You have been bathing regularly, haven’t you?”. When we arrive at the front door of the cottage, Big Joe is waiting for us inside, his face lights up.

“Tommuiluvuilu” he cries (at least, that’s what it sounds like), and he wraps his arms so tightly around me and Mother that I feel as if we will be crushed.

“Alright, Joe”, says mother “give him some room to breathe!” and at last, we are released. “Now,” says Mother, showing me inside, “there’s someone else who would like to say hello.”

I remember when I was very young, everyone else seemed so huge, and I spent most of my life looking directly up at people while crawling about on the floor. It was as if I existed in a different universe to everyone else, for they were all huge compared to me, ate different foods, lived different lives, and talked in a language which I did not yet understand. In short, grown-ups were a different species.

Now, mother takes me into the kitchen and shows me a most wonderful sight. In the corner, wrapped in bright yellow blankets, is little Tommo. He is, without a doubt, the most adorable little creature I have ever laid eyes upon, with wide blue eyes, a tiny, button-like nose and small, round ears. For a moment, as I look at him, the burden of Charlie’s death, and of every other problem in the world seems to briefly evaporate. I then get a feeling of having come full circle, for I am now the giant, looking down at the tiny baby from high above, thinking back to when I was that size, and wondering exactly when I became the almost adult that I am now. Eventually, mother snapped me out of it.

“Isn’t he beautiful, just like you all were.” she said “Oh, and to think one day he might be going to France…” she stopped herself, visibly on the verge of tears. For a moment, we had nothing to say, but then Big Joe started coughing again, and mother rushed to give him a handkerchief.

When Molly arrived, it was almost sunset, and Big Joe, though still visibly excited about me being back, had eventually been forced into bed. Mother was in the kitchen, getting ready to make dinner, and I was in the front room, looking after little Tommo. I heard her walking across the garden, and hurried to the front door. I knew she was expecting me to be there, but she acted surprised when she saw me, she hugged me tightly and started telling me all about the colonel’s sudden decision to cut everyone’s wages, and how the Wolfwoman nearly fell down the stairs. We sat together for dinner, talking about life in the trenches and back home. At last, I felt as if we were part of a family again. But those feelings were short-lived, for then Molly said

“So, what really happened? To Charlie, I mean.”

Right now I am still trying to give them an answer, Molly and Mother are staring at me expectantly, and the only thing breaking the awkward silence is Little Tommo’ s gurgling. At last I speak.

“Charlie wasn’t a coward.” I say “He was shot because Hanley didn’t like him. The sergeant told the platoon to go and charge right into the enemy firing lines. Charlie said we’d all be killed, that it’d be stupid and he wasn’t going. He was right, and all. Only half of the soldiers who went out ever came back. Unfortunately, Hanley did, and I bet he was annoyed that Charlie was right and he was wrong. Anyone else would’ve admitted that, but not Hanley.” I realise that Mother has a tear on her cheek, but I keep going, “Charlie got court martialled, then shot for cowardice!” Molly bursts into tears, then the baby wakes up and starts crying. Mother comforts Molly, but Molly does not want it. She walks over to little Tommo, and through her own tears she tries to comfort him by singing Oranges and Lemons in her sweet voice. I cannot bear it anymore, and storm outside. Eventually, Mother comes out, she sees me staring down at the earth scornfully. She puts her arm around me and says

“It isn’t your fault that Charlie died; if you had tried to save him you would have been shot as well. War is no playtime, Tommo, and sometimes you have to give up the people you love.”. Mother is right, Charlie was destined to die from the moment he signed up. Then I remember how the Colonel ordered us to join the army, ordered us to go and threatened to evict us. My mind is filled with images of the cruel Colonel, the Wicked Wolfwoman and Horrible Hanley, all being shot to pieces in No-Man’s-Land while we watch from the trenches, me, Molly, Mother, Big Joe and Little Tommo. Charlie is there too, with Father and Bertha. I wish it could be true, that we could be together again, forever. I look up to the stars, where, somewhere, Bertha is howling and Charlie and Father are saying

“We’re always here for you, Tommo, always.”

Mother walks me back into the cottage and together we sing Oranges and Lemons as we slowly start to adjust to life without Charlie. It will be tough, but I think I’ll manage.

-

Molly’s Letters

An imagining of the sort of letter which Molly would have sent to Thomas and Charlie as they went away to join the army.

Dear Tommo

By the time you are in a position to read this letter, you will be well on your way out of Iddesleigh and into the war. I do not know how we will manage without you back home. Already, things are starting to change. The colonel has told us that, with nearly all the men gone from the estate, I’m going to have to take on additional jobs. I now have to work from six o’clock in the morning to six at night.

The worst problems, though, are back at home. At the time of writing, it is still three hours before you leave, and already Big Joe is getting worried. We might not be able to hide the truth from him for so much as a week, let alone the many months for which you will be away. But even then, there is always the chance that you and Charlie don’t come back.

I know I probably shouldn’t be frightening you like this at this time, but everywhere I go, I hear about how our troops are being slaughtered, our defences overrun. I wonder how many people from our village are going to come back in one piece. I’m so worried about you, Tommo, and about Charlie, too. I can’t bear the thought of living the rest of my life without you, or of raising the baby on my own.

I know that you are in charge of your own life now, but promise me this, Tommo, promise me that when you get out onto the battlefield, you give the Germans a good kick up the backside for me.

Love from

Molly

*

Dear Charlie

The more I think about you, and where you are going, the more I am starting to miss you. After being with you for many years, I don’t know how I shall adapt to us being apart. You are the most wonderful man I have ever known. I know that most people would disagree. They would point out how you stole Bertha and got me pregnant, but I don’t care, I love you in a way that they could never understand. I have to live without you now, and I don’t know how I’ll cope.

I now have to work twelve hours a day for the Colonel and the Wolfwoman, while you go off to slaughter the Germans. The colonel says that getting rid of you was the best thing to do, and that you need to find out how to become a man. I don’t see why he cannot go to fight in the war, being a colonel.

Back at home, Big Joe is already getting suspicious, and mother is looking ever more depressed. She says that we have to look happy for you, and that we must not cry when you get on the train. Even if I manage to hold back the tears, I will be crying inside. I don’t want to have to say goodbye to my husband so soon. But, I have to look on the bright side. Hopefully all will go well and you will be back home before the baby is born.

Your mother keeps reminding me that we need to start getting ready to look after the infant; we’re going to go out next week to but some new bed sheets and blankets, and perhaps some toys for the baby to play with. Of course, we don’t yet know whether or not the baby will be a girl, but your mother and the people around the village are continually referring to it as my “daughter”. With any luck, (s)he will have his/her father alongside them as they grow up. I would hate to have to raise her alone. Try to beat the Germans quickly and come home soon.

Love

Your Wife Molly